Chris Edwards

Those acquainted with English history know that in 1215 AD, land-owning barons pressed King John to approve the Magna Carta, which limited his power and helped secure individual liberties. John “was a very poor king” who “levied frequent taxes,” according one history on my bookshelf.

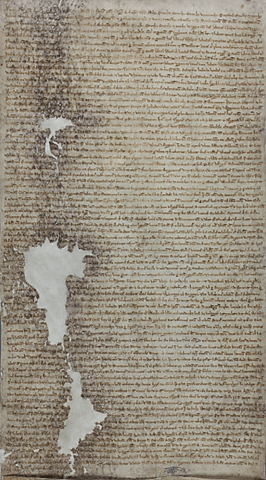

However, an article in BBC History magazine informs me that “Magna Carta” historically referred to a revised 1225 version of the charter. It is this later version that influenced government and law in England for centuries. So, happy 800th birthday, Magna Carta.

The battles to rein in kings and limit government power went on for centuries. The Magna Carta formed the basis of subsequent statutes and played a key role in educating each generation about their liberties. But even before the early 1200s, the Magna Carta had precursors, including a “Charter of Liberties” issued by King Henry I in 1100 AD.

America’s limited-government Founding could not have happened without the centuries of struggle and progress made by the English. Our National Archives holds a 1297 version of the Magna Carta, courtesy of David Rubenstein. The Archives Foundation notes, “Magna Carta also guaranteed due process of law, freedom from arbitrary imprisonment, trial by a jury of peers, and other fundamental rights that inspired and informed the Founding Fathers of our nation when they wrote the Declaration of Independence, United States Constitution, and Bill of Rights.”

Some people worry that our current president is acting like an unhinged king, such as the chaotic way he is unilaterally imposing hefty trade barriers. Interestingly, the Magna Carta tried to guard against this precise abuse: “All merchants are to be safe and secure in departing from and coming to England, and in their residing and movements in England, by both land and water, for buying and selling, without any evil exactions but only paying the ancient and rightful customs.” (Clause 41 of the 1215 charter).

Here are excerpts from the BBC History article by David Carpenter, a professor of medieval history at King’s College, London:

That [1215] document, sealed under duress from rebel barons and famously subjecting the king to the law and promising justice to all, is widely lauded today as a milestone in the establishment of English law. Yet the fact is that, in the centuries after 1215, the term Magna Carta was hardly ever used for John’s document. Rather, that was the name given to the charter issued nearly a decade later by King John’s son, Henry III, at Westminster on 11 February 1225.

Although Henry’s charter was based on his father’s, the earlier iteration was usually called simply the “Charter of Runnymede.” So when, in 1297 and 1300, Henry’s son Edward I confirmed Magna Carta, he meant the charter of 1225—and the same was true of all later confirmations.

King John quashed the 1215 charter, and the barons deposed him. In 1217, John’s minor son, King Henry III, and his court made another deal with the barons to issue a new version of the charter. This charter was

accompanied by an entirely new charter regulating the running of the royal forest. It was at this point that the term Magna Carta (“Great Charter”) was first introduced, referring not to its grandeur by to its size, to distinguish that larger charter from the smaller Charter of the Forest.

In 1225, a grown Henry III wanted to fight a war in France to be funded by higher taxes, and he needed buy-in from the barons. He agreed to a new version of the Magna Carta. The 1215 and 2025 versions were cowritten by Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

For Langton, one of the great biblical scholars of the age, [the charter] responded to deeply held ideas about the need for rulers to be limited by the law.

… Langton, responding to ideas about how just rule should benefit the whole community, also did something to make Magna Carta more inclusive. The concessions in the charters of 1216 and 1217, like those in 1215, had been made only to people who were free—thus excluding the unfree peasantry who made up the largest part of the population. In 1225, this changed. The statement that the concessions had been made to the free remained, but it was qualified—indeed, contradicted by the new preamble in which these concessions were granted to “everyone in the kingdom.”

Carpenter notes that the Magna Carta was not without flaws, but

The texts of the charters also became widely known and, thus, sank deep roots into English society. Copies were made by religious houses, magnates, ministers, knights, freemen and lawyers. Of the various versions, that of 1225 was easily the most copied.

… Those examining the texts—and marginal annotations bear witness to intensive study—could see that Magna Carta was far more than just a baronial document. Chapters such as those regulating the levying of fines and the running of local government benefited wide sections of society.